The Francis effect

About to take over a crisis-ridden company with a demoralised workforce? Turn to a Roman case study

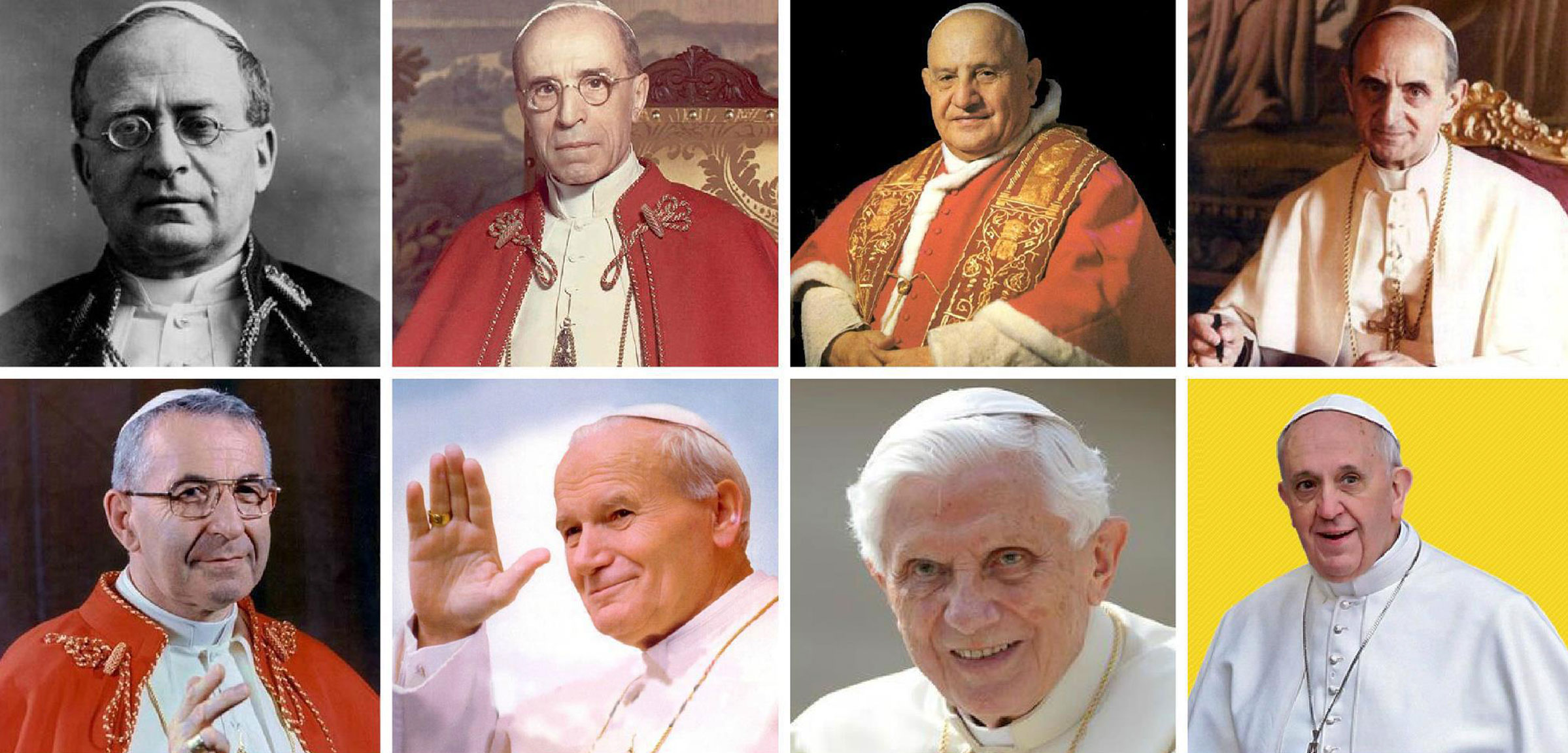

BUSINESS schools regularly teach their students about great “turnaround CEOs” who breathe new life into dying organisations: figures such as IBM’s Lou Gerstner, Fiat’s Sergio Marchionne and Apple’s Steve Jobs. Now Harvard Business School needs to add another case study: Jorge Bergoglio, the man who has rebranded RC Global in barely a year.

When Pope Francis celebrated his first Easter as CEO, just after being appointed, the world’s oldest multinational was in crisis. Pentecostal competitors were stealing market share in the emerging world, including in Latin America, where Francis ran the Argentine office. In its traditional markets, scandals were scaring off customers and demoralising the salesforce. Recruitment was difficult, despite the offer of lifetime employment in a tough economy. The firm’s finances were also a mess. Leaked documents revealed the Vatican bank as a vortex of corruption and incompetence. The board was divided and weak. Francis’s predecessor, Benedict XVI, was the first pope to resign for 600 years, amid dark rumours that the founder and chairman, a rarely seen elderly bearded figure whose portrait adorns the Sistine boardroom, had intervened.

Operating prophet

In just a year, the business has recovered a lot of its self-confidence. The CEO is popular: 85% of American Catholics—a tough audience—approve of him. Footfall in RC Global’s retail outlets is rising again. The salesforce now talks about a “Francis effect”. How has a septuagenarian Argentine succeeded in galvanising one of the world’s stodgiest outfits? Essentially by grasping three management principles.

The first is a classic lesson in core competences. Francis has refocused his organisation on one mission: helping the poor. One of his first decisions was to forsake the papal apartments in favour of a boarding house which he shares with 50 other priests and sundry visitors. He took the name of a saint who is famous for looking after the poor and animals. He washed and kissed the feet of 12 inmates of a juvenile-detention centre. He got rid of the fur-trimmed velvet capes that popes have worn since the Renaissance, swapped Benedict’s red shoes for plain black ones and ignored his fully loaded Mercedes in favour of a battered Ford.

This new focus has allowed the company to spend fewer resources on ancillary businesses, such as engaging in doctrinal disputes or staging elaborate ceremonies. The “poor-first strategy” is also aimed squarely at emerging markets, where the potential for growth is greatest but competition fiercest.

Along with the new strategic focus, the pope is employing two management tools to good effect. One is a brand repositioning. He clearly continues to support traditional teaching on abortion and gay marriage, but in a less censorious way than his predecessors (“Who am I to judge?” he asked of homosexuals). The other is a restructuring. He has appointed a group of eight cardinals (“the C8”) to review the church’s organisation and brought in McKinsey and KPMG (“God’s consultants”) to look at the church’s administrative machinery and overhaul the Vatican bank.

Will it work? Established critics, notably the corporate raider Lou Siffer, maintain it is all incense-smoke and mirrors. Others insist that more sweeping change, including a bigger role for women, is needed. The chairman’s attitude is unknown. Some analysts interpret the absence of plagues of boils and frogs as approbation; others point out that He moves in mysterious ways, his wonders to perform.

Fuente: the economist